Psychotherapy / Psychoanalysis

INTENSIVE DYNAMIC PSYCHOTHERAPY

and

PSYCHOANALYSIS

web notes

THOMAS M. BROD, MD

There are certain difficulties with the UCLA BOL server (tied to security) that make it difficult to blog with the program I use. However, I invite readers to send comments to me via email (tbrod@ucla.edu) and I will attempt to post/respond here.

ARTICLES (click to link)

-

What is ISTDP? 7-25-08

-

An oldie, but goodie Davanloo article 6-6-08

-

Bettleheim on the psychoanalytic attitude 10-14-08

-

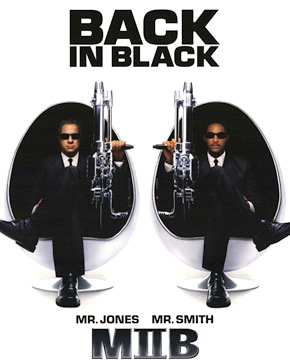

Movies: Anality in MEN IN BLACK 7-19-09

-

INTENSIVE ALLIANCES in Psychotherapy 11-14-09

-

Psychotherapy Better Than Money for Happiness? 12-1-09

- Evidence Accumulates: Dynamic Psychotherapy Endures Effectively 10-10-10

-

ISTDP article on Psychology Today Blog

11-14-11

ISTDP article on Psychology Today Blog

November 15, 2011

Patricia Coughlin, co-author of the splendid text, Lives Transformed: A Revolutionary Method of Dynamic Psychotherapy is quoted extensively in a blog posted yesterday. Use this link. On the same page are links to articles on "Defense Mechanisms" and another on "15 Crazy Things About Vaginas." All worthwhile reading.

Evidence Accumulates: Dynamic Insight Psychotherapy Endures Effectively

October 10, 2010

A recent review in the Harvard Mental Health Letterconfirms that there is data that insight-oriented dynamic psychotherapy is an effective treatment--which actually improves function after the formal treatment has finished. It concludes, "There is now enough research available to support the claim that psychodynamic therapy is an evidence-based treatment with effect sizes similar to or superior to those reported for other psychotherapies... Yet it is encouraging that the benefits of psychodynamic therapy not only endure after therapy ends, but increase with time. This suggests that insights gained during psychodynamic therapy may equip patients with psychological skills that grow stronger with use."

The Merits of Psychodynamic Therapy in the Harvard Mental Health Letter, Volume 27, Number 3, September 2010

December 1, 2009

Psychotherapy may increase happiness more than money, researchers say. The American Psychiatric Association has brought this intriguing study to my attention.

HealthDay (11/28, Preidt) reported that, according to a study published online Nov. 18 in the journal Health Economics, Policy and Law, "psychological therapy may be much more effective at making people happy than getting a raise or winning a lottery prize." University of Warwick "researchers analyzed data on thousands of people who provided information about their mental well-being and found that the increase in happiness from a $1,329 course of therapy was so significant that it would take a pay raise of more than $41,542 to achieve an equal boost in well-being." This "suggests that therapy could be as much as 32 times more cost-effective at improving well-being than simply getting more money," the authors said.

Intensive Alliances in Psychotherapy.

In psychotherapy, there is an essential need for a working relationship, an alliance between patient (client) and therapist.

We bend toward each other, syncing up our personalities, deepening the connection, looking together for attachment points that will restore some old lost balance in the patient.

In all psychoanalytic psychotherapy, the task is to get below the surface of the patient's life, so the patient can learn and do something about their disturbances. What complicates the task is that the conscious intention of most patients is confounded by unconscious avoidance of emotional closeness when painful old issues are stirred up. Therapists with different types of training and theoretical orientation will handle these so-called "attachment" issues differently, but the essential task is common to all.

Habib Davanloo MD (see earlier posts here) has developed a very effective framework for approaching the many unconscious resistances to emotional closeness and the attendant symptoms such as anxiety, sleep and physical disturbances, and self-defeating behavior patterns. I have just taught a new course for advanced mental health professionals, called Working with Intense Dynamic Alliances. The key slides for that course are posted on another page of this web site. Click here to look them over.

July 19, 2009

I came across this article by HH Stein on the International Psychoanalysis website. An interesting piece on unconscious development in the human mind, exemplified in a very funny film. How naturally we forget!

Our ability to control powerful, primitive emotions and fantasies is linked to the developmental achievement of sphincter control of our bowels. Learning to control our bowels gives us a model for controlling our emotions. The film, Men in Black, gives life to the struggle between the wish to express and to suppress “primal (murderous, cannibalistic) affect.” It is our ability to suppress our primitive emotions and fantasies, to “not know about it,” that allows us (..more)

October 14, 2008

Psychoanalysis is a process in which two minds engage in the deepest dialogue possible about one of them. No one’s experience in psychoanalytic treatment will be duplicated, even remotely, by another’s experience. With such infinite variety, it is no wonder the field is understood so differently by different people. Nor, that it is so widely misunderstood.

My colleague, David James Fisher has recently published an important critical biography of Bruno Bettelheim. In an early chapter, he communicates a vital perspective on psychoanalysis. I have quoted that section below, changing only the verb tense very slight alterations to help the quotation stand alone.

Bettelheim made a number of pronouncements about psychoanalytic theory and practice. First: what it is not. Psychoanalysis is not about making life easy; it is not the amelioration of isolated symptoms; it is not about adjustment to existing social or political status quo; it is not a system of intellectual constructs or abstractions; it is not the sole prerogative of the physician or the medical and biological disciplines; it is not a religion; it is not about the purveying of an esoteric or revealed body of truth; it is not a positivistic or pragmatic form of knowing whose results can be replicated, predicted, or statistically measured.

For Bettelheim, psychoanalysis was first and foremost a human science of the spirit, part of a tradition of secular hermeneutics, that is, an introspective form of self-understanding that relied on the exploration of unconscious and symbolic meanings. As an ideographic science, psychoanalysis belonged to the human sciences where the method is historical, archeological, and, above all, interpretative. Psychoanalytic insight threatens our narcissistic image of ourselves; it reveals that the “I” is not the master of its own house, thus injuring our self-love and our self-esteem. Profound self-knowledge always turns on the exploration of the individual’s most shameful, most incestuous, and most destructive internal forces. Above all else, Bettelheim argued that psychoanalysis is part of an endless process where an individual resumes a stunted developmental course, aspiring toward or approximating psychological maturity. Its insights enhanced the capacity of an individual to acquire a moral education, learning how to act and behave ethically. In attempting to wring some meaning out of our existence, psychoanalysis accepts the problematic and tragic nature of life without being defeated and without giving in to escapism. [from Bettelheim: Living and Dying, JDFisher, 2008, Rodopi, pp 22-23. Note that I have altered some past-tense verbs to present-tense to highlight that these notions are not “past” but currently pertinent. tmb] return to top of page

July 25, 2008

What is Intensive Short-term Dynamic Psychotherapy, ISTDP?

Allan Abbass, MD, at Dalhousie University in Halifax Canada is the world's most productive researcher in the field of Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. He and his group have demonstrated positive outcomes in patients with a wide variety of diagnostic areas such as depression, anxiety, somatization, substance abuse, eating disorders and personality problems. What follows is his most recent description of ISTDP from their web site. For access to the published papers click on the link at the end.

Intensive Short-term Dynamic Psychotherapy or ISTDP is a form of brief psychotherapy developed by Davanloo of McGill University, taught in several international training programs including ours, and actively researched by our Centre here in Halifax.

The basic ISTDP understanding of many psychological disorders is based on attachment and the emotional effects of broken attachments. Interruptions and trauma to human attachments may cause a cascade of complex emotions which may become blocked and avoided. When later life events stir up these feelings, anxiety and defences may be activated. This basic finding was derived from a large case series by Davanloo in the 1960-70‘s.

These anxiety and defences maybe totally unconscious to the person doing them, and the result is ruined relationships, physical symptoms and a range of psychiatric symptoms. A proportion of all patients with anxiety, depression, substance use, and interpersonal problems have this emotional blockage problem.

These processes can lead to negative health effects in every system in the body including the gastrointestinal tract, cardiovascular system, respiratory system, immune system, muscular system and skin. The anxiety and defences can lead to increased worry about the body, and negative interactions with the health care system. Additionally, these problems can lead to disability and depression secondarily.

The treatment approach ISTDP as designed by Davanloo, is first to acquaint the patient with these unconscious processes and then to help them to overcome the emotional blocking processes. This often means a focus on the feelings the patient has in the office during the moments of the interview and pointing out the ways the patient blocks off both the emotions and the connection with the therapist in treatment.

When these feelings are experienced there is an abrupt drop in tension, anxiety and other physical symptoms and defences. Thus, the patient and therapist can then see the driving emotional forces that were being defended. Thereafter a healing process may occur in which the old avoided feelings are experienced and worked through. Often one of these breakthroughs is enough to bring about major symptom improvement, while in most cases a series of these events are required to bring about major behavioral changes. If the patient has very low tolerance of anxiety, a treatment process in group or individual therapy may be required first to build this up before the emotions can be experienced.

At the end of a successful therapy, there is an absence of somatic anxiety and major defences, so health and relationships are free to develop and persist as they were meant to before the original trauma.

This treatment and variants of it have been extensively researched and shown effective with some patients with depression, anxiety, somatization, substance abuse, eating disorders and personality problems.

Click this link for access to papers and summaries: http://psychiatry.medicine.dal.ca/centreforemotions/media.htm#publications

June 6, 2008

A pretty good historical introduction to Habib Davanloo's Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy (IS-TDP)...

The following article was published in the New York Times in 1982! I am going to use it to intitiate this blog-type page. With the exception of a significant reportorial error that I've marked, the article is still quite good. Of course, the STDP field has matured in the 26 years since this article was published. Davanloo himself has evolved his thinking and technique; plus his students from around the world have grown in various directions.

A NEW AND CONTROVERSIAL SHORT-TERM PSYCHOTHERAPY

By DAVA SOBEL; DAVA SOBEL, A FORMER REPORTER FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES, WRITES FREQUENTLY ON MENTAL-HEALTH SUBJECTS.

Published: November 21, 1982

Like a drowning man, Richard Jones was floundering in panic, losing hold on his life. A multitude of phobias made it impossible for him to drive a car, board an airplane, ride the subway, enter an elevator or be alone in an open space. The thought of going to a movie or to a restaurant paralyzed him with fear that the place might catch fire and that he would be trapped inside. As he became more frightened, he grew increasingly depressed and was plagued by chronic headaches. Richard's efforts to get help - seven years in treatment with two psychotherapists and attendance at a special phobia clinic - had failed. Desperation made him test one more hope of cure - a psychiatrist who specializes in an unusual form of brief therapy.Within six weeks, Richard began to feel positive signs of change. After 32 hourlong sessions, he was completely cured, and in a followup meeting with the therapist four years later, Richard could honestly report that not one of his symptoms had ever returned.

I can testify to the speed and apparent total recovery of Richard because I watched the therapy on television. The name Richard Jones is made up, but the long-suffering man is real; he is an executive with a large engineering concern in Montreal.

Richard's psychiatrist videotaped every moment of the process, from the initial assessment interview through a series of annual checkups. An essential part of Richard's treatment was to look at the tapes and see himself as he was when therapy began.

But the psychiatrist also had another motive: He wanted evidence to show that this form of therapy was effective, and that other doctors could learn the technique by watching it. In fact, I watched the tapes with four traditionally trained psychiatrists at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York who were struggling to master the technique.

This is the first time that an approach to therapy has been so clearly demonstrable, so open to evaluation. It makes a therapist conducting an analytic hour as accountable as a surgeon performing an appendectomy.

The treatment, called ''short-term dynamic psychotherapy,'' is the most aggressive form of psychic medicine to rest on the principles of Sigmund Freud. The therapist plays an active, confrontational role, instead of the silent, supportive stance used by many psychotherapists in long-term treat-ment. He forces the patients to plumb the source of their problem behavior in 15 to 40 sessions, rather than waiting until the patients are ''ready'' to bring up painful experiences. The therapist actually badgers them into discussing these episodes, refusing to let the patients shy away from discussion or cover up their emotions.

Though wedded to psychoanalytic principles, the technique rejects Freud's process of total free association, in which the patients are allowed to talk at random about anything that comes to mind. Here, the therapist directs the course of conversation with specific goals in mind. In psychoanalysis and other long-term treatments, the desired end may never be explicitly defined.

Patients who enter short-term dynamic psychotherapy must be able to express their chief complaints, so that therapy goals can be set. Vague disturbances, such as ''everything is wrong,'' make patients ineligible, whereas long-term treatments afford them the time to explore general malaise.

While some other time-limited approaches to psychotherapy also use confrontational techniques, this one has the unusual addition of the video camera, which allows patient and therapist alike to review the course of treatment. Change, when it comes, is the result of breaking down the resistance that separates patients' thoughts from their feelings, thus making them able to cope with situations that had paralyzed them before. Since the course of care is brief, the cost is comparatively low - an attractive feature in this highly psychologically minded society with limited treatment resources and increasing doubts about the kind of psychotherapy that drags on for years.

Proponents of short-term dynamic psychotherapy claim that it can be used successfully with as many as 35 percent of the people who report to psychiatric outpatient clinics for counseling, making it potentially the most widely applicable of the several hundred psychotherapies practiced today.

Opponents, however, dismiss the very idea of quick cures for longstanding problems because, they say, years spent hiding in fear or acting out in anger will not be reversed by such a brief course of therapy. Says one authority on psychotherapy research: ''I've been around too long to believe in miracles.'' Others question the basic concept of harassing a patient into health, fearful that the harsh treatment will only create deeper scars. Still others attack the video recording: So what if it contributes to scientific validation, they complain, when it makes such a mockery of patient confidentiality?

Short-term dynamic psychotherapy is a sharply defined adaptation of psychoanalytic principles. One would like to have a more colloquial term for it - ''brief therapy'' perhaps - but ''brief therapy'' includes a score of other concepts. These range from the single-session therapy originated by Bernard L. Bloom of the University of Colorado to the time-limited therapy of James Mann at the Boston University School of Medicine, as well as the ''focused problem resolution'' treatment developed at the Mental Research Institute in Palo Alto, Calif. And often, ''brief therapy'' turns out to be a euphemism for ''aborted therapy,'' or for long-term approaches cut short by insurance-company time limits.

Although short-term dynamic psychotherapy has existed in various stages of research and refinement for about 20 years, it is just burgeoning into a recognizable force, drawing converts and controversy.

In practice, the therapist relentlessly badgers patients to demolish the defenses they have built around their feelings. {{Blogger's note: although the therapist may be "relentless" in applying Davanloo's method, badgering and attempts by the therapist to demolishing defenses would be major, fundamental, technical errors that would ruin the therapeutic alliance. Treatment is a collaborative effort. TMB}}Every time they smile, pause or use an expression that conveys doubt (''I guess,'' ''I suppose''), the doctor seizes the opportunity to challenge them, often evoking a storm of emotion. At first the emotions tend to be anger at the therapist, which may be extremely difficult for the patients to express. But the doctor encourages them to let it come out, and throws the light from this friction back into their buried memories, eventually piercing through to the driving engine of their neuroses. In traditional long-term psychotherapy this process is expected to take many years.

In the course of treatment, Richard Jones was not taught how to modify his behavior or how to overcome specific fears or how to change self-defeating patterns of thought. He received no tranquilizers for his anxiety. What he had was a quasi psychoanalysis in an extraordinarily condensed and controlled form. And although his symptoms were never the target of the work he did in therapy, they vanished as a result of it.

Since February of this year, three new institutes for teaching and research in short-term dynamic psychotherapy have opened - in New York City, Woodcliff Lake, N.J., and Charlottesville, Va. All are modeled on existing centers in London, Montreal, New York and Hartford, Conn. Another is scheduled to open soon in Madrid, Spain, and plans for another center are being negotiated with the University of California at San Diego. But this handful of centers will barely begin to accommodate the hundreds of psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers seeking training.

Practitioners accepted into programs give up almost all their free time for at least one and usually two years of rigorous study and supervision, no matter how long they have been practicing or how well schooled they are in analytic principles. Most of them consent because they see short-term dynamic psychotherapy as the savior of a demoralized profession - a brand of therapy that does not rely on drugs, gimmicks or cult figures, that brings rapid results, that has been documented on videotape and that offers hope to perhaps thousands of individuals who might not receive any kind of treatment under the current structure of mental health care.

But patients give up an incredible degree of privacy in the bargain. Indeed, since the videoptape exposes so much more than even the most explicit notes from an analyst's files or audio tapes of analytic sessions, I had to sign a specially drafted agreement before being allowed to view the episodes mentioned in this article. (The doctors justified showing me material previously reserved for psychotherapists only, they said, on the ground that they considered my writing to be public education. Patients had been told that their tapes might be used for educational purposes.)

I looked at photos of all the patients before viewing their tapes so that I could assure the doctors I didn't know any of them personally. I had to promise not to discuss the cases with my friends or colleagues and not to write about any of the patients who lived in New York ''no matter how disguised'' my descriptions might be. The only exception to this last condition is a Beth Israel patient I shall call Grace Bloom, who volunteered to talk with me. Other vignettes presented here are drawn from the archives of the Canadian clinic where short-term dynamic psychotherapy was first practiced in the early 1960's.

According to statistical estimates made in the mid-1970's by the National Institute of Mental Health, people who could benefit from some form of psychotherapy account for at least 15 percent of the American population, or upward of 30 million people. Of these, roughly 1 percent have severe disturbances, such as schizophrenia or major depression of psychotic proportions, which are treated with drugs or hospitalization or both, in addition to psychotherapy. An unspecified number of the remaining 14 percent are not ''sick'' by anyone's definition, but have so-called ''problems of everyday living'' - the stresses of unemployment, for example, empty-nest syndrome or a prolonged grief reaction to the death of a loved one - that disable them. The rest suffer from neuroses, personality disorders and severe but not suicidal depression.

All but the 1 percent seriously debilitated could be considered possible candidates for short-term dynamic psychotherapy. To be accepted for treatment they must demonstrate, in two evaluation sessions with two different therapists, that they have the psychological strength to tolerate the anxiety generated by the technique. Individuals who ''come unglued under the pressure,'' as one doctor described it, are referred to other forms of psychotherapy. Short-term dynamic psychotherapy was conceived by Dr. Habib Davanloo, associate professor of psychiatry at McGill University and director of outpatient psychiatric services at the Montreal General Hospital, who now devotes most of his time to teaching it. A fellow of both the American and Canadian Psychiatric Associations, Dr. Davanloo lectures on his technique at the annual meetings of these groups, as well as at dozens of smaller symposiums and workshops he conducts each year in North America and Europe. He has made more than 200 such presentations since 1970, most of them in the last five years. He also coordinated three international congresses on the several forms of brief therapy held in 1975, 1976 and 1977 (two in Montreal and the last, which drew 1,300 professionals, in Los Angeles).

At 54, the Iranian-born analyst is fast becoming recognized as the doyen of brief psychotherapy -whether he is being lauded or damned for that distinction.

Enthusiasm for short-term dynamic psychotherapy began to rise at the 1977 international congress. It was there that the British psychiatrist Dr. David H. Malan, who spent 25 years developing his own version of brief therapy, gave up on his method and made arrangements to become Dr. Davanloo's student. He now travels to Montreal two or three times a year for two weeks of ''immersion training'' in the technique, which he is using and teaching at the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations in London.

''Freud discovered the unconscious,'' Dr. Malan said. ''Davanloo has discovered how to use it therapeutically.'' Many traditional analysts, however, consider it a sacrilege to mention Dr. Davanloo and Freud in the same breath. Here is the way Dr. George E. Gross, medical director of the treatment center at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute, compares psychoanalysis with shortterm dynamic psychotherapy:

''It's the difference between an archeological dig and a treasure hunt,'' Dr. Gross said. ''That's not to say that people are not rewarded by the things they find on a treasure hunt, but if you're an archeologist, you're interested in something else. Psychoanalysis has the potential to uncover an entire civilization.''

Dr. Gross also said that the confrontational tactics used by Dr. Davanloo create ''an atmosphere'' that may interfere with the work of self-exploration. ''You can't carry out an archeological dig in the middle of an earthquake,'' he said.

Dr. Gross, though familiar with Dr. Davanloo's work, has not seen the videotapes. Nor has he ever watched another analyst at work under any circumstances. This is the ''psychoanalytic privilege'' that shrouds all such doctor-patient exchanges in secrecy.

Those interested in proving the efficacy of one or another therapeutic approach, however - whether their aim is pure research or providing better public service or convincing insurance companies that mental-health coverage is worthwhile - are more interested in tangible evidence.

For example, Hans H. Strupp, Distinguished Professor of Psychology at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., and an authority in psychotherapy research, has headed numerous programs funded by the National Institute of Mental Health to try to determine which forms of psychotherapy work best for whom and what the outcome is likely to be in various chief of research and program evaluation in psychiatry after three years as director of the South Beach Psychiatric Center on Staten Island. ''Your own unconscious is stimulated. You have to be very careful of what you say, and yet you must not miss the opportunity to say certain things.

''In traditional psychoanalysis,'' adds Dr. Trujillo, who has practiced both, ''supervisors always tell you, 'When in doubt, say nothing.' You always get another crack at the material because free association will bring it up again and again if you wait long enough. That's not the case here.''

Dr. Winston and Dr. Trujillo, along with their colleagues, including Dr. Harold Been and Dr. Victor Goldin, have been in training with Dr. Davanloo for two years. They all have long professional experience, are teachers of psychoanalytic theory and veteran analysands themselves; yet they maintain that they could not have mastered the technique in less than one year of intensive study. Even now, Dr. Davanloo still spends one weekend each month in New York with them, viewing their tapes in his role as supervisor and showing them his tapes to teach by example.

The tapes are such an essential part of the therapeutic process that patients who object to the video recording are not accepted for treatment.

''Most of our patients take about a minute to forget the camera,'' Dr. Goldin said. ''Therapists, on the other hand, take longer. Maybe six months. It's hard for us to look at ourselves.''

''When you expose yourself this way,'' Dr. Winston added, ''you put your professional reputation on the line.'' According to Dr. Trujillo, the video camera is doing for psychotherapy what the microscope did for biology: once you have seen the subvisual world through the microscope, you stop inventing demons and magic as the agents of change. Similarly, when you have documented the course of change in a human life on videotape, you stop accepting vague descriptions of what ''change'' means.

''Psychotherapy has traditionally been very loose in this respect,'' Dr. Trujillo explained. ''Therapists say things like, 'Well, the patient is still impotent, but now he doesn't mind.' ''

Beyond its role as research tool, the video camera is also a safety net and a partner in the treatment. At group evaluation meetings like this one, all the therapists admit to seeing things on tape that they might never have thought to write a note about. And because they pore over every session at least once and usually twice, with the benefit of colleagues' comments, they feel more confident that they are pursuing the right issues. All of this contributes to the brevity and, they say, the effectiveness of the treatment.

''I was in therapy myself for 800 hours,'' Dr. Goldin said. ''The course of treatment here can be as little as 800 minutes.'' Six months after the end of therapy, patients are invited back for the first of several follow-up meetings in which they view randomly selected segments of their sessions and discuss the treatment, its impact on their lives and, of course, their feelings then and now. Each of these post-mortems is also videotaped - a play within a play where the patient on videotape watches himself on videotape and offers play-by-play commentary.

''I can't believe I was ever so masochistic,'' one woman remarked with a laugh at one such session. ''I think I would sooner become a sadist than ever go back to the way I was.''

Patients I watched at this stage had a sense of personal accomplishment. Their comments were typically: ''It was very hard work that went on here. But I did the job. You helped.'' One of them said: ''The change I feel is not something you put in my head.''

Patients did not come to see the therapist as an idealized or superhuman figure. Therapy ended with no agonizing over termination, no sense of clinging.

Students of short-term dynamic psychotherapy believe that these positive effects result from preventing the development of the transference neurosis, which shortens treatment for the patients but makes training for the therapists arduous and long. This is particularly true if they have been schooled in classical analysis.

Why would any established analyst agree to go through it? ''Because it brings the magic back,'' Dr. Goldin answered. ''Many people my age - I'm 55 - entered psychiatry because we enjoyed psychoanalysis and dynamic therapy both theoretically and in practice. A lot has happened since those days. We've seen the public grow more psychologically minded but also disenchanted with the length of time needed for treatment. We've seen the introduction of drugs, behavior modification, group therapy.

''Frankly,'' he went on, ''pharmacology holds lesser interest for me, but as a psychiatrist I've dispensed my share of drugs since the 1950's. Now along comes Davanloo with something that lets us help people the old way, using all the analytic tools, and yet it works quickly and you can study it just as you would a new medication. I haven't been so excited since I was in analytic school.'' Dr. Davanloo began to conceptualize his technique in reaction to unsettling events in his own early training at Boston's Massachusetts General Hospital and the six years he spent in psychoanalysis.

As a young psychiatric resident in the outpatient clinic at one of the country's major teaching hospitals, Dr. Davanloo was ''demoralized,'' he recalls, when he came to understand the state of long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Patients assigned to him for treatment had been kept on clinic waiting lists for two to three years because the limited staff was overburdened with its existing caseload.

He saw some of his patients about two hours a week for one year, but when his year of supervised training was over he terminated treatment, turning the cases over to another doctor.

What happens over time because of this practice, which is standard operating procedure nationwide, he observed, is that the residents go on to become professors in the medical school but the patients are never cured. ''In fact they are made worse,'' he said. ''They get transference neurosis upon transference neurosis from being switched from one doctor to another until finally the transference neurosis becomes institutionalized and they are hooked on the hospital as a fathermother figure for the rest of their lives.''

Accepting the fact that true long-term care was an unattainable goal in most outpatient clinics, he set about devising his own form of brief therapy. His decision to jump from an attitude of quiet support to one of relentless challenge, however, was inspired by spending time on the couch himself. ''There I would be in my analyst's office and the telephone would ring,'' he said. ''And he would answer it! My whole free association would be disrupted by this and created in me a total irritation toward him. And I would hold down my irritation, but then I would become silent. And he was also silent, totally ignoring what was taking place. And then, at the end, he would say, 'Tomorrow.' ''

Dr. Davanloo wondered why it had to be that way -all that good fury wasted by ignoring it. Why didn't the analyst try to hold on and ride it home to the core of the neurosis? In his own approach, Dr. Davanloo vowed, he would not let such opportunities pass him by.

''When the patient comes,'' he said, ''immediately I am focusing on the patient's feelings. I am constantly, actively involved.'' Thus he altered free association, Freud's passive technique of letting the patient lie down and talk about whatever comes to mind, and replaced it with ''focused free association.'' Free association plodded an unnecessarily circuitous route through the psyche, he thought. You couldn't tell where it would take you or for how long. There were no existing studies regarding its effectiveness - and it seemed that there never would be any.

Ironically, it was Freud himself who conducted the first brief psychoanalytic therapy in 1906 when he treated the conductor Bruno Walter in six sessions. Several years later, he cured Gustav Mahler's impotence in four hours.

Other early forays into brief alternatives were cited by Dr. Judd Marmor of Los Angeles in a historical review he presented at the Third International Symposium on Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. These included the ''active therapy'' of Sandor Ferenczi, the ''will therapy'' of Otto Rank and the therapeutic technique practiced by Franz Alexander.

''There are still individuals in the psychoanalytic movement,'' Dr. Marmor said, ''who view the development of short-term techniques of dynamic psychotherapy as a regrettable debasement of the pure gold of psychoanalysis.''

But brief therapy seems to be a pragmatic necessity today. As Dr. Christ L. Zois, medical director of the new International Institute for Teaching and Research in Short-Term Intensive Dynamic Psychotherapy in New York, explained: ''It is a luxury for therapists to put all our training into one patient for five years. When you consider how many people can benefit from treatment, even the difference between 10 and 15 sessions is great.''

Dr. Davanloo bemoans the fact that many people who become excited about short-term dynamic psychotherapy at a symposium or workshop begin to use some part of it without really knowing how to apply the whole. Then the therapist loses control of the case, he said, while the patient feels battered instead of badgered in his own interest.

The point is that only those therapists trained by Dr. Davanloo or his disciples, to put it harshly, can practice short-term dynamic psychotherapy effectively. And the claim smacks of the often-quoted quip that all one needs to start a school of psychotherapy is a charismatic figure and a building.

But there are important differences here. One is the willingness to make instruction accessible, whereas founders of numerous other psychotherapeutic styles have never even published their techniques. Another is the body of supporting research - and the possibility for future research - comparing short-term dynamic psychotherapy with other approaches. And last, of course, are the volumes of videotape that strip Dr. Davanloo of any mystique he might otherwise enjoy.

return to top